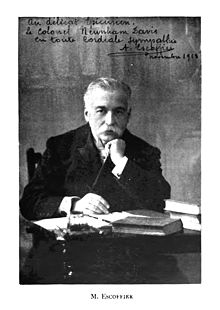

Escoffier :

Escoffier is The Master Chef!

French Classical Cuisine and most styles of modern cuisine can be traced back to his works. (I can think of no person that has done more for the Culinary Arts than this man.)

His Five Mother Sauces are a necessity, of your knowledge base, that you must master if you are serious about sauces in your cooking.

If you have read my feeling about Escoffier on the Heritage Food Network Home Page you know that I have nothing but the deepest respect for his talent, ability and contribution to the Culinary World.

So, now I am going to share Escoffier's lessons of the Five Mother Sauces, that will change the way you look at making sauces forever.

He discusses and teaches the Five Mother Sauces. This is the base for every sauce that is made, this is a time tested truth that is arguably indisputable. Learn these sauces and you will be able to create sauces that will have those you cook for drooling for more and more.

Espagnole sauce

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Espagnole sauce (French pronunciation: [ɛspaɲɔl]) is one of the mother sauces that are the basis of sauce-making in classic French cooking. In the late 19th century, Auguste Escoffier codified the recipe, which is still followed today.[1]Espagnole has a strong taste and is rarely used directly on food.

As a mother sauce, however, it serves as the starting point for many derivatives, such as Sauce Africaine, Sauce Bigarade, Sauce Bourguignonne, Sauce aux Champignons, Sauce Charcutière, Sauce Chasseur, Sauce Chevreuil and Demi-glace. There are hundreds of other derivatives in the classical French repertoire.

Escoffier included a recipe for a Lenten Espagnole sauce, using fish stock and mushrooms, in Le Guide culinaire but doubted its necessity.

Espagnole SauceGourmet | December 2004http://www.epicurious.com Epicurus

Espagnole Sauce

yield: Makes about 2 2/3 cups

active time: 35 min

total time: 8 hr (includes making stock)

Espagnole is a classic brown sauce, typically made from brown stock, mirepoix, and tomatoes, and thickened with roux. Given that the sauce is French in origin, where did the name come from? According to Alan Davidson, in The Oxford Companion to Food, "The name has nothing to do with Spain, any more than the counterpart term allemande has anything to do with Germany. It is generally believed that the terms were chosen because in French eyes Germans are blond and Spaniards are brown." Cook carrot and onion in butter in a 3-quart heavy saucepan over moderate heat, stirring occasionally, until golden, 7 to 8 minutes. Add flour and cook roux over moderately low heat, stirring constantly, until medium brown, 6 to 10 minutes. Add hot stock in a fast stream, whisking constantly to prevent lumps, then add tomato purée, garlic, celery, peppercorns, and bay leaf and bring to a boil, stirring. Reduce heat and cook at a bare simmer, uncovered, stirring occasionally, until reduced to about 3 cups, about 45 minutes.

Pour sauce through a fine-mesh sieve into a bowl, discarding solids.

*Available at some specialty foods shops and cooking.com (stock requires a dilution ratio of 1:16; 1/4 cup concentrate to 4 cups water).

Cooks' note: Sauce can be made 1 day ahead and cooled completely, uncovered, then chilled, covered.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Hollandaise sauce served over white asparagus and potatoes.

Hollandaise sauce is an emulsion of egg yolk and butter, usually seasoned with lemon juice, salt, and a littlewhite pepper or cayenne pepper. In appearance it is light yellow and opaque, smooth and creamy. The flavor is rich and buttery, with a mild tang added by the seasonings, yet not so strong as to overpower mildly-flavored foods.

Hollandaise is one[1] of the five sauces in the French haute cuisine mother sauce repertoire. It is so named because it was believed to have mimicked a Dutch sauce for the state visit to France of the King of the Netherlands. Hollandaise sauce is well known as a key ingredient of Eggs Benedict, and is often paired with vegetables such as steamed asparagus.

Bechamel or Sauce BéchamelFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Bechamel is a standard white sauce and one of the five "leading sauces" of classical cuisine. It's the starting point for other classic sauces such as the Crème sauce and the Mornay sauce.

Béchamel is a simple, versatile sauce that you'll find yourself making again and again.

Béchamel sauce

Béchamel sauce is a key ingredient in many lasagna recipes.

Béchamel sauce (English: /bɛʃəˈmɛl, beɪʃəˈmɛl/[1] French: [beʃamɛl], Italian: besciamella [beʃʃaˈmɛlla]), also known as white sauce, is one of the mother sauces of French cuisine and is used in many recipes of the Italian cuisine, e.g.lasagne emiliane. It is used as the base for other sauces (such as Mornay sauce, which is Béchamel with cheese). It is traditionally made by whisking scalded milk gradually into a white flour-butter roux (equal parts clarified butter and flour by weight). Another method, considered less traditional, is to whisk kneaded flour-butter (beurre manié) into scalded milk. The thickness of the final sauce depends on the proportions of milk and flour.

Also see these 7 Béchamel Sauce Variations.

Prep Time: 5 minutesCook Time: 20 minutesTotal Time: 25 minutesIngredients:

Hollandaise Sauce

Epicurious | February 1962 Barbara Poses Kafka

yield: Makes 2 cups, or enough for a broiled unseasoned steak serving 4 to 6

The preparation of most hot butter sauces has as its object the relatively permanent and smooth blending together of ingredients. The grand-daddy of these sauces is Hollandaise. Here is the classic

Use a small, thick ceramic bowl set in a heavy-bottomed pan, or a heavyweight double boiler. Off the heat, put the egg yolks and cream in the bowl or upper section of the double boiler and stir with a wire whisk until well-blended — the mixture should never be beaten but stirred, evenly, vigorously and continually. Place the container over hot water (if you are setting the bowl in water, there should be about 1 1/2 inches of water in the pan; in a double boiler, the water should not touch the top section). Stirring eggs continuously, bring the water slowly to a simmer. Do not let it boil. Stir, incorporating the entire mixture so there is no film at the bottom. When the eggs have thickened to consistency of very heavy cream, begin to add the cooled melted butter with one hand, stirring vigorously with the other. Pour extremely slowly so that each addition is blended into the egg mixture before more is added. When all the butter has been added, add the lemon juice or vinegar a drop at a time and immediately remove from heat. Add salt and a mere dash of cayenne.Note: If you proceed with care your Hollandaise should not curdle. If it does, however, don't despair. Finish adding the butter as best you can. Remove sauce to a small bowl, clean the pot and put a fresh egg yolk in it. Start over again, using the curdled sauce as if it were the butter.

Velouté sauce

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

velouté sauce, along with Allemande, Béchamel, and Espagnole, is one of the sauces of French cuisine that were designated the four "mother sauces" by Antonin Carême in the 19th century. The French chef Auguste Escoffier later classified tomato, mayonnaise, and hollandaise among mother sauces as well. The term velouté is from the French adjectival form of velour, meaning velvety.In preparing a velouté sauce, a light stock (one in which the bones used have not been previously roasted), such as chicken, veal or fish stock, is thickened with a blond roux. Thus the ingredients of a velouté are equal parts by mass butter and flour to form the roux, a light chicken, veal, or fish stock, and salt and pepper for seasoning. Commonly the sauce produced will be referred to by the type of stock used e.g. chicken velouté.[1]

Velouté sauce

Chicken Velouté Sauce

Velouté is one of the "leading sauces" of classical cuisine. It can be made with any white stock, including veal stock, or fish stock, but this version, the chicken velouté, is made with chicken stock and is the most common.

Chicken velouté is the basis for the traditional Supreme Sauce, as well as the classic Mushroom sauce, the Aurora sauce and many others.

Note that the velouté is not itself a finished sauce — that is to say, it isn't typically served as is. You could, however, simply season it with salt and pepper and use it much as you would a basic gravy.

Prep Time: 5 minutes

Cook Time: 30 minutes

Total Time: 35 minutes

Ingredients:

· 6 cups chicken stock

· 2 Tbsp clarified butter

· 2 Tbsp all-purpose flour

Preparation:

1. Heat the chicken stock to a simmer in a medium saucepan, then lower the heat so that the stock just stays hot.

2. Meanwhile, in a separate heavy-bottomed saucepan, melt the clarified butter over a medium heat until it becomes frothy. Don't let it turn brown, though — that'll affect the flavor.

3. With a wooden spoon, stir the flour into the melted butter a little bit at a time, until it is fully incorporated into the butter, giving you a pale-yellow-colored paste. This paste is called a roux. Heat the roux for another minute or so to cook off the taste of raw flour.

4. Using a wire whisk, slowly add the hot chicken stock to the roux, whisking vigorously to make sure it's free of lumps.

5. Simmer for about 30 minutes or until the total volume has reduced by about one-third, stirring frequently to make sure the sauce doesn't scorch at the bottom of the pan. Use a ladle to skim off any impurities that rise to the surface.

6. The resulting sauce should be smooth and velvety. If it's too thick, whisk in a bit more hot stock until it's just thick enough to coat the back of a spoon.

7. Remove the sauce from the heat. For an extra smooth consistency, carefully pour the sauce through a wire mesh strainer lined with a piece of cheesecloth.

8. Keep the velouté covered until you're ready to use it.

Makes about 1 quart of chicken velouté sauce.

Tomato Sauce Escoffier’s Sauce Tomat Recipe:

I got this interpretation of The Escoffier Tomat Recipe from Jacob Burton, the host of the Free Culinary School Podcast.

Although most of the sauce recipes that I’ve been giving for the Mother Sauces yield 1 quart (1 liter), this recipe will yield 2 quarts since you can almost never have enough tomato sauce, and it is always better the next day anyways.

For Escoffier’s recipe you will need:

2-3 oz (56-84 g) Salt Pork. Salt pork comes from the belly portion of the pig, just like bacon. However, unlike bacon, salt pork is never smoked, and the fattier (more white), the better.

3 oz (84 g) Carrots, peeled and medium diced

3 oz (84 g) White or Yellow onion, medium diced

2 oz (56 g) whole butter

2-3 oz (56-84 g) Flour, All Purpose

5 lbs (2.25 Kilos) Raw, Good quality tomatoes, quartered

1 qt (1 lt) White Veal Stock

1 clove freshly crushed garlic

Salt and Pepper To taste

Pinch of Sugar

1. In his book, Escoffier calls for you to “fry the salt pork in the butter until the pork is nearly melted.” The term frying can be misleading, and what he’s really calling for you to do is to render the fat.

2. To render out the salt pork properly, place the salt pork in a heavy bottom sauce pan with a tablespoon of water, cover with a lid, and place over medium heat. Check in about 5 minutes. The steam from the water will allow the fat to render out of the salt pork before it starts to brown or burn.

3. After the salt pork is nice and rendered out, add in your butter, carrots and onions, and sweat over medium heat for about 5-10 minutes, or until they become nice and tender and start to release their aromatic aromas.

4. Sprinkle the flower over the carrots and onions and continue to cook for another few minutes. You’re essentially using the residual fat from the butter and salt pork to make a blond roux.

5. Add in your raw tomatoes. Roast with other ingredients until they start to soften and release some of their liquid.

6. Add in your white veal stock and a clove of crushed garlic.

7. Cover the pot with a lid, and Escoffier says to put it in a moderate oven, which is about 350 degrees F or 175 C. If your sauce pot won’t fit, you can always just simmer it on your stove top. Bake in oven or simmer for 1.5-2 hours.

8. Escoffier’s classical recipe also calls for you to pass your finished sauce through a Tamis, but if you’re looking for a smooth tomato sauce, I would instead recommend that you first blend it in a blender, and then press it through a chinois.

9. Once you have passed your sauce through the chinois, finish by seasoning it with salt, pepper, and a pinch of sugar.

10 Note on Sugar: The addition of sugar is used to balance the natural acidity of the tomatoes. Your tomato sauce should not taste sweet, unless you enjoy putting ketchup on your pasta.

Modern Variations on Escoffier’s Sauce Tomat

The major difference between Escoffier’s version of sauce tomat and modern variations that are taught in culinary school are two fold.

(1), The Roux is omitted and instead of using fresh tomatoes, canned tomatoes and tomato puree are used in the respective ratio of 2:1 and, (2) Instead of using white veal stock, modern recipes call for the simmering of a roasted ham bone.

Other than that, the process is pretty much the same as discussed above. Follow the same recipe and process, except use 3lbs of canned tomatoes and 2lbs of tomato puree instead of the 5lbs of fresh tomatoes. Simmer for two hours with the addition of a roasted ham bone and omit the veal stock since the tomato puree and canned tomatoes offer plenty liquid for simmering the sauce.

Another modern touch is the common use of aromatic fresh herbs including bay leafs, thyme, basil and oregano. Add these at your own discretion, at the end of the cooking process so that the flavor of the fresh herbs does not break down.

Tomato sauceFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A tomato sauce is any of a very large number of sauces made primarily from tomatoes, usually to be served as part of a dish (rather than as a condiment). Tomato sauces are common for meat and vegetables, but they are perhaps best known as sauces for pasta dishes.

Tomatoes have a rich flavour, high liquid content, very soft flesh which breaks down easily, and the right composition to thicken into a sauce when they are cooked (without the need of thickeners like roux). All of these qualities make them ideal for simple and appealing sauces. The simplest tomato sauces consist just of chopped tomato flesh (with the skins and seeds optionally removed), cooked in a little olive oil and simmered until it loses its raw flavour, and seasoned with salt.

Water (or another, more flavorful liquid such as stock or wine) is often added to keep it from drying out too much.Onion and garlic are almost always sweated or sautéed at the beginning before the tomato is added. Other seasonings typically include basil, oregano, parsley, and possibly some spicy red pepper or black pepper. Ground or chopped meat is also common.

In countries such as Australia and New Zealand, in southern Africa and the United Kingdom the term 'tomato sauce' is used to describe a condiment similar to that known in the USA as 'ketchup'.[1] In Britain, both terms are used for the condiment.

French Classical Cuisine and most styles of modern cuisine can be traced back to his works. (I can think of no person that has done more for the Culinary Arts than this man.)

His Five Mother Sauces are a necessity, of your knowledge base, that you must master if you are serious about sauces in your cooking.

If you have read my feeling about Escoffier on the Heritage Food Network Home Page you know that I have nothing but the deepest respect for his talent, ability and contribution to the Culinary World.

So, now I am going to share Escoffier's lessons of the Five Mother Sauces, that will change the way you look at making sauces forever.

He discusses and teaches the Five Mother Sauces. This is the base for every sauce that is made, this is a time tested truth that is arguably indisputable. Learn these sauces and you will be able to create sauces that will have those you cook for drooling for more and more.

Espagnole sauce

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Espagnole sauce (French pronunciation: [ɛspaɲɔl]) is one of the mother sauces that are the basis of sauce-making in classic French cooking. In the late 19th century, Auguste Escoffier codified the recipe, which is still followed today.[1]Espagnole has a strong taste and is rarely used directly on food.

As a mother sauce, however, it serves as the starting point for many derivatives, such as Sauce Africaine, Sauce Bigarade, Sauce Bourguignonne, Sauce aux Champignons, Sauce Charcutière, Sauce Chasseur, Sauce Chevreuil and Demi-glace. There are hundreds of other derivatives in the classical French repertoire.

Escoffier included a recipe for a Lenten Espagnole sauce, using fish stock and mushrooms, in Le Guide culinaire but doubted its necessity.

Espagnole SauceGourmet | December 2004http://www.epicurious.com Epicurus

Espagnole Sauce

yield: Makes about 2 2/3 cups

active time: 35 min

total time: 8 hr (includes making stock)

Espagnole is a classic brown sauce, typically made from brown stock, mirepoix, and tomatoes, and thickened with roux. Given that the sauce is French in origin, where did the name come from? According to Alan Davidson, in The Oxford Companion to Food, "The name has nothing to do with Spain, any more than the counterpart term allemande has anything to do with Germany. It is generally believed that the terms were chosen because in French eyes Germans are blond and Spaniards are brown." Cook carrot and onion in butter in a 3-quart heavy saucepan over moderate heat, stirring occasionally, until golden, 7 to 8 minutes. Add flour and cook roux over moderately low heat, stirring constantly, until medium brown, 6 to 10 minutes. Add hot stock in a fast stream, whisking constantly to prevent lumps, then add tomato purée, garlic, celery, peppercorns, and bay leaf and bring to a boil, stirring. Reduce heat and cook at a bare simmer, uncovered, stirring occasionally, until reduced to about 3 cups, about 45 minutes.

Pour sauce through a fine-mesh sieve into a bowl, discarding solids.

*Available at some specialty foods shops and cooking.com (stock requires a dilution ratio of 1:16; 1/4 cup concentrate to 4 cups water).

Cooks' note: Sauce can be made 1 day ahead and cooled completely, uncovered, then chilled, covered.

- 1 small carrot, coarsely chopped

- 1 medium onion, coarsely chopped

- 1/2 stick (1/4 cup) unsalted butter

- 1/4 cup all-purpose flour

- 4 cups hot beef stock or reconstituted beef-veal demi-glace concentrate*

- 1/4 cup canned tomato purée

- 2 large garlic cloves, coarsely chopped

- 1 celery rib, coarsely chopped

- 1/2 teaspoon whole black peppercorns

- 1 Turkish or 1/2 California bay leaf

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Hollandaise sauce served over white asparagus and potatoes.

Hollandaise sauce is an emulsion of egg yolk and butter, usually seasoned with lemon juice, salt, and a littlewhite pepper or cayenne pepper. In appearance it is light yellow and opaque, smooth and creamy. The flavor is rich and buttery, with a mild tang added by the seasonings, yet not so strong as to overpower mildly-flavored foods.

Hollandaise is one[1] of the five sauces in the French haute cuisine mother sauce repertoire. It is so named because it was believed to have mimicked a Dutch sauce for the state visit to France of the King of the Netherlands. Hollandaise sauce is well known as a key ingredient of Eggs Benedict, and is often paired with vegetables such as steamed asparagus.

Bechamel or Sauce BéchamelFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Bechamel is a standard white sauce and one of the five "leading sauces" of classical cuisine. It's the starting point for other classic sauces such as the Crème sauce and the Mornay sauce.

Béchamel is a simple, versatile sauce that you'll find yourself making again and again.

Béchamel sauce

Béchamel sauce is a key ingredient in many lasagna recipes.

Béchamel sauce (English: /bɛʃəˈmɛl, beɪʃəˈmɛl/[1] French: [beʃamɛl], Italian: besciamella [beʃʃaˈmɛlla]), also known as white sauce, is one of the mother sauces of French cuisine and is used in many recipes of the Italian cuisine, e.g.lasagne emiliane. It is used as the base for other sauces (such as Mornay sauce, which is Béchamel with cheese). It is traditionally made by whisking scalded milk gradually into a white flour-butter roux (equal parts clarified butter and flour by weight). Another method, considered less traditional, is to whisk kneaded flour-butter (beurre manié) into scalded milk. The thickness of the final sauce depends on the proportions of milk and flour.

Also see these 7 Béchamel Sauce Variations.

Prep Time: 5 minutesCook Time: 20 minutesTotal Time: 25 minutesIngredients:

- 5 cups whole milk

- 6 Tbsp clarified butter (or ¾ stick unsalted butter)

- 1/3 cup all-purpose flour

- ¼ onion, peeled

- 1 whole clove

- Kosher salt, to taste

- Ground white pepper, to taste

- Pinch of ground nutmeg (optional)

- In a heavy-bottomed saucepan, bring the milk to a simmer over a medium heat, stirring occasionally and taking care not to let it boil.

- Meanwhile, in a separate heavy-bottomed saucepan, melt the clarified butter over a medium heat until it becomes frothy. Don't let it turn brown, though — that'll affect the flavor.

- With a wooden spoon, stir the flour into the melted butter a little bit at a time, until it is fully incorporated into the butter, giving you a pale-yellow-colored paste. This paste is called a roux. Heat the roux for another minute or so to cook off the taste of raw flour.

- Using a wire whisk, slowly add the hot milk to the roux, whisking vigorously to make sure it's free of lumps.

- Now stick the pointy end of the clove into the onion and drop them into the sauce.Simmer for about 20 minutes or until the total volume has reduced by about 20 percent, stirring frequently to make sure the sauce doesn't scorch at the bottom of the pan.

- The resulting sauce should be smooth and velvety. If it's too thick, whisk in a bit more milk until it's just thick enough to coat the back of a spoon.

- Remove the sauce from the heat. You can retrieve the clove-stuck onion and discard it now. For an extra smooth consistency, carefully pour the sauce through a wire mesh strainer lined with a piece of cheesecloth.

- Season the sauce very lightly with salt and white pepper. Be particularly careful with the white pepper — and the nutmeg, if you're using it. A little bit goes a long way! Keep the béchamel covered until you're ready to use it.

Hollandaise Sauce

Epicurious | February 1962 Barbara Poses Kafka

yield: Makes 2 cups, or enough for a broiled unseasoned steak serving 4 to 6

The preparation of most hot butter sauces has as its object the relatively permanent and smooth blending together of ingredients. The grand-daddy of these sauces is Hollandaise. Here is the classic

Use a small, thick ceramic bowl set in a heavy-bottomed pan, or a heavyweight double boiler. Off the heat, put the egg yolks and cream in the bowl or upper section of the double boiler and stir with a wire whisk until well-blended — the mixture should never be beaten but stirred, evenly, vigorously and continually. Place the container over hot water (if you are setting the bowl in water, there should be about 1 1/2 inches of water in the pan; in a double boiler, the water should not touch the top section). Stirring eggs continuously, bring the water slowly to a simmer. Do not let it boil. Stir, incorporating the entire mixture so there is no film at the bottom. When the eggs have thickened to consistency of very heavy cream, begin to add the cooled melted butter with one hand, stirring vigorously with the other. Pour extremely slowly so that each addition is blended into the egg mixture before more is added. When all the butter has been added, add the lemon juice or vinegar a drop at a time and immediately remove from heat. Add salt and a mere dash of cayenne.Note: If you proceed with care your Hollandaise should not curdle. If it does, however, don't despair. Finish adding the butter as best you can. Remove sauce to a small bowl, clean the pot and put a fresh egg yolk in it. Start over again, using the curdled sauce as if it were the butter.

- 3 egg yolks

- 1 tablespoon cream

- 1 cup (1/2 pound) melted butter, cooled to room temperature

- 1 tablespoon lemon juice or white wine vinegar

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- Dash of cayenne pepper

Velouté sauce

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

velouté sauce, along with Allemande, Béchamel, and Espagnole, is one of the sauces of French cuisine that were designated the four "mother sauces" by Antonin Carême in the 19th century. The French chef Auguste Escoffier later classified tomato, mayonnaise, and hollandaise among mother sauces as well. The term velouté is from the French adjectival form of velour, meaning velvety.In preparing a velouté sauce, a light stock (one in which the bones used have not been previously roasted), such as chicken, veal or fish stock, is thickened with a blond roux. Thus the ingredients of a velouté are equal parts by mass butter and flour to form the roux, a light chicken, veal, or fish stock, and salt and pepper for seasoning. Commonly the sauce produced will be referred to by the type of stock used e.g. chicken velouté.[1]

Velouté sauce

Chicken Velouté Sauce

Velouté is one of the "leading sauces" of classical cuisine. It can be made with any white stock, including veal stock, or fish stock, but this version, the chicken velouté, is made with chicken stock and is the most common.

Chicken velouté is the basis for the traditional Supreme Sauce, as well as the classic Mushroom sauce, the Aurora sauce and many others.

Note that the velouté is not itself a finished sauce — that is to say, it isn't typically served as is. You could, however, simply season it with salt and pepper and use it much as you would a basic gravy.

Prep Time: 5 minutes

Cook Time: 30 minutes

Total Time: 35 minutes

Ingredients:

· 6 cups chicken stock

· 2 Tbsp clarified butter

· 2 Tbsp all-purpose flour

Preparation:

1. Heat the chicken stock to a simmer in a medium saucepan, then lower the heat so that the stock just stays hot.

2. Meanwhile, in a separate heavy-bottomed saucepan, melt the clarified butter over a medium heat until it becomes frothy. Don't let it turn brown, though — that'll affect the flavor.

3. With a wooden spoon, stir the flour into the melted butter a little bit at a time, until it is fully incorporated into the butter, giving you a pale-yellow-colored paste. This paste is called a roux. Heat the roux for another minute or so to cook off the taste of raw flour.

4. Using a wire whisk, slowly add the hot chicken stock to the roux, whisking vigorously to make sure it's free of lumps.

5. Simmer for about 30 minutes or until the total volume has reduced by about one-third, stirring frequently to make sure the sauce doesn't scorch at the bottom of the pan. Use a ladle to skim off any impurities that rise to the surface.

6. The resulting sauce should be smooth and velvety. If it's too thick, whisk in a bit more hot stock until it's just thick enough to coat the back of a spoon.

7. Remove the sauce from the heat. For an extra smooth consistency, carefully pour the sauce through a wire mesh strainer lined with a piece of cheesecloth.

8. Keep the velouté covered until you're ready to use it.

Makes about 1 quart of chicken velouté sauce.

Tomato Sauce Escoffier’s Sauce Tomat Recipe:

I got this interpretation of The Escoffier Tomat Recipe from Jacob Burton, the host of the Free Culinary School Podcast.

Although most of the sauce recipes that I’ve been giving for the Mother Sauces yield 1 quart (1 liter), this recipe will yield 2 quarts since you can almost never have enough tomato sauce, and it is always better the next day anyways.

For Escoffier’s recipe you will need:

2-3 oz (56-84 g) Salt Pork. Salt pork comes from the belly portion of the pig, just like bacon. However, unlike bacon, salt pork is never smoked, and the fattier (more white), the better.

3 oz (84 g) Carrots, peeled and medium diced

3 oz (84 g) White or Yellow onion, medium diced

2 oz (56 g) whole butter

2-3 oz (56-84 g) Flour, All Purpose

5 lbs (2.25 Kilos) Raw, Good quality tomatoes, quartered

1 qt (1 lt) White Veal Stock

1 clove freshly crushed garlic

Salt and Pepper To taste

Pinch of Sugar

1. In his book, Escoffier calls for you to “fry the salt pork in the butter until the pork is nearly melted.” The term frying can be misleading, and what he’s really calling for you to do is to render the fat.

2. To render out the salt pork properly, place the salt pork in a heavy bottom sauce pan with a tablespoon of water, cover with a lid, and place over medium heat. Check in about 5 minutes. The steam from the water will allow the fat to render out of the salt pork before it starts to brown or burn.

3. After the salt pork is nice and rendered out, add in your butter, carrots and onions, and sweat over medium heat for about 5-10 minutes, or until they become nice and tender and start to release their aromatic aromas.

4. Sprinkle the flower over the carrots and onions and continue to cook for another few minutes. You’re essentially using the residual fat from the butter and salt pork to make a blond roux.

5. Add in your raw tomatoes. Roast with other ingredients until they start to soften and release some of their liquid.

6. Add in your white veal stock and a clove of crushed garlic.

7. Cover the pot with a lid, and Escoffier says to put it in a moderate oven, which is about 350 degrees F or 175 C. If your sauce pot won’t fit, you can always just simmer it on your stove top. Bake in oven or simmer for 1.5-2 hours.

8. Escoffier’s classical recipe also calls for you to pass your finished sauce through a Tamis, but if you’re looking for a smooth tomato sauce, I would instead recommend that you first blend it in a blender, and then press it through a chinois.

9. Once you have passed your sauce through the chinois, finish by seasoning it with salt, pepper, and a pinch of sugar.

10 Note on Sugar: The addition of sugar is used to balance the natural acidity of the tomatoes. Your tomato sauce should not taste sweet, unless you enjoy putting ketchup on your pasta.

Modern Variations on Escoffier’s Sauce Tomat

The major difference between Escoffier’s version of sauce tomat and modern variations that are taught in culinary school are two fold.

(1), The Roux is omitted and instead of using fresh tomatoes, canned tomatoes and tomato puree are used in the respective ratio of 2:1 and, (2) Instead of using white veal stock, modern recipes call for the simmering of a roasted ham bone.

Other than that, the process is pretty much the same as discussed above. Follow the same recipe and process, except use 3lbs of canned tomatoes and 2lbs of tomato puree instead of the 5lbs of fresh tomatoes. Simmer for two hours with the addition of a roasted ham bone and omit the veal stock since the tomato puree and canned tomatoes offer plenty liquid for simmering the sauce.

Another modern touch is the common use of aromatic fresh herbs including bay leafs, thyme, basil and oregano. Add these at your own discretion, at the end of the cooking process so that the flavor of the fresh herbs does not break down.

Tomato sauceFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A tomato sauce is any of a very large number of sauces made primarily from tomatoes, usually to be served as part of a dish (rather than as a condiment). Tomato sauces are common for meat and vegetables, but they are perhaps best known as sauces for pasta dishes.

Tomatoes have a rich flavour, high liquid content, very soft flesh which breaks down easily, and the right composition to thicken into a sauce when they are cooked (without the need of thickeners like roux). All of these qualities make them ideal for simple and appealing sauces. The simplest tomato sauces consist just of chopped tomato flesh (with the skins and seeds optionally removed), cooked in a little olive oil and simmered until it loses its raw flavour, and seasoned with salt.

Water (or another, more flavorful liquid such as stock or wine) is often added to keep it from drying out too much.Onion and garlic are almost always sweated or sautéed at the beginning before the tomato is added. Other seasonings typically include basil, oregano, parsley, and possibly some spicy red pepper or black pepper. Ground or chopped meat is also common.

In countries such as Australia and New Zealand, in southern Africa and the United Kingdom the term 'tomato sauce' is used to describe a condiment similar to that known in the USA as 'ketchup'.[1] In Britain, both terms are used for the condiment.

Auguste Escoffier

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Escoffier" redirects here. For other uses, see Escoffier (disambiguation).

Auguste Escoffier

Born28 October 1846

Georges Auguste Escoffier (28 October 1846 – 12 February 1935) was a French chef, restaurateur and culinary writer who popularized and updated traditional French cooking methods. He is a legendary figure among chefs and gourmets, and was one of the most important leaders in the development of modern French cuisine. Much of Escoffier's technique was based on that of Antoine Carême, one of the codifiers of French haute cuisine, but Escoffier's achievement was to simplify and modernize Carême's elaborate and ornate style. Referred to by the French press as roi des cuisiniers et cuisinier des rois ("king of chefs and chef of kings"[1], though this had also been previously said of Carême), Escoffier was France's pre-eminent chef in the early part of the 20th century.

Alongside the recipes he recorded and invented, another of Escoffier's contributions to cooking was to elevate it to the status of a respected profession by introducing organized discipline to his kitchens. He organized his kitchens by the brigade de cuisine system, with each section run by a chef de partie.

Escoffier published Le Guide Culinaire, which is still used as a major reference work, both in the form of a cookbook and a textbook on cooking. Escoffier's recipes, techniques and approaches to kitchen management remain highly influential today, and have been adopted by chefs and restaurants not only in France, but also throughout the world.[2]

Contents [hide][edit]Ritz HotelsIn 1897, César Ritz and Escoffier were both dismissed from the Savoy Hotel. Ritz and Echenard were implicated in the disappearance of over £3400 of wine and spirits, and Escoffier had been receiving gifts from the Savoy's suppliers.[3] By this time, however, Ritz and his colleagues were already on the point of commercial independence, having established the Ritz Hotel Development Company, for which Escoffier set up the kitchens and recruited the chefs, first at the Paris Ritz (1898), and then at the new Carlton Hotel in London (1899), which soon drew much of the high-society clientele away from the Savoy.[4] In addition to the haute cuisine offered at luncheon and dinner, tea at the Ritz became a fashionable institution in Paris, and later in London, though it caused Escoffier real distress: "How can one eat jam, cakes and pastries, and enjoy a dinner – the king of meals – an hour or two later? How can one appreciate the food, the cooking or the wines?"[5]

In 1913, Escoffier met Kaiser Wilhelm II on board the SS Imperator, one of the largest ocean liners of the Hamburg-Amerika Line. The culinary experience on board the Imperator was overseen by Ritz-Carlton, and the restaurant itself was a reproduction of Escoffier's Carlton Restaurant in London. Escoffier was charged with supervising the kitchens on board the Imperator during the Kaiser's visit to France. One hundred and forty-six German dignitaries were served a large multi-course luncheon, followed that evening by a monumental dinner that included the Kaiser's favourite strawberry pudding, named fraises Imperator by Escoffier for the occasion. The Kaiser was so impressed that he insisted on meeting Escoffier after breakfast the next day, where, as legend has it, he told Escoffier, "I am the Emperor of Germany, but you are the Emperor of Chefs." This was quoted frequently in the press, further establishing Escoffier's reputation as France's pre-eminent chef.[6]

Ritz gradually moved into retirement after opening The Ritz Hotel in 1906, leaving Escoffier as the figurehead of the Carlton until his own retirement in 1920. He continued to run the kitchens through World War I, in which his younger son was killed in active service.[4] Recalling these years, The Times said, "Colour meant so much to Escoffier, and a memory arises of a feast at the Carlton for which the table decorations were white and pink roses, with silvery leaves – the background for a dinner all white and pink, Borscht striking the deepest note,Filets de poulet à la Paprika coming next, and the Agneau de lait forming the high note."[7]

[edit]DeathEscoffier died on 12 February 1935, at the age of 88 in Monte Carlo, a few days after the death of his wife.

[edit]Publications

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Escoffier" redirects here. For other uses, see Escoffier (disambiguation).

Auguste Escoffier

Born28 October 1846

Georges Auguste Escoffier (28 October 1846 – 12 February 1935) was a French chef, restaurateur and culinary writer who popularized and updated traditional French cooking methods. He is a legendary figure among chefs and gourmets, and was one of the most important leaders in the development of modern French cuisine. Much of Escoffier's technique was based on that of Antoine Carême, one of the codifiers of French haute cuisine, but Escoffier's achievement was to simplify and modernize Carême's elaborate and ornate style. Referred to by the French press as roi des cuisiniers et cuisinier des rois ("king of chefs and chef of kings"[1], though this had also been previously said of Carême), Escoffier was France's pre-eminent chef in the early part of the 20th century.

Alongside the recipes he recorded and invented, another of Escoffier's contributions to cooking was to elevate it to the status of a respected profession by introducing organized discipline to his kitchens. He organized his kitchens by the brigade de cuisine system, with each section run by a chef de partie.

Escoffier published Le Guide Culinaire, which is still used as a major reference work, both in the form of a cookbook and a textbook on cooking. Escoffier's recipes, techniques and approaches to kitchen management remain highly influential today, and have been adopted by chefs and restaurants not only in France, but also throughout the world.[2]

Contents [hide][edit]Ritz HotelsIn 1897, César Ritz and Escoffier were both dismissed from the Savoy Hotel. Ritz and Echenard were implicated in the disappearance of over £3400 of wine and spirits, and Escoffier had been receiving gifts from the Savoy's suppliers.[3] By this time, however, Ritz and his colleagues were already on the point of commercial independence, having established the Ritz Hotel Development Company, for which Escoffier set up the kitchens and recruited the chefs, first at the Paris Ritz (1898), and then at the new Carlton Hotel in London (1899), which soon drew much of the high-society clientele away from the Savoy.[4] In addition to the haute cuisine offered at luncheon and dinner, tea at the Ritz became a fashionable institution in Paris, and later in London, though it caused Escoffier real distress: "How can one eat jam, cakes and pastries, and enjoy a dinner – the king of meals – an hour or two later? How can one appreciate the food, the cooking or the wines?"[5]

In 1913, Escoffier met Kaiser Wilhelm II on board the SS Imperator, one of the largest ocean liners of the Hamburg-Amerika Line. The culinary experience on board the Imperator was overseen by Ritz-Carlton, and the restaurant itself was a reproduction of Escoffier's Carlton Restaurant in London. Escoffier was charged with supervising the kitchens on board the Imperator during the Kaiser's visit to France. One hundred and forty-six German dignitaries were served a large multi-course luncheon, followed that evening by a monumental dinner that included the Kaiser's favourite strawberry pudding, named fraises Imperator by Escoffier for the occasion. The Kaiser was so impressed that he insisted on meeting Escoffier after breakfast the next day, where, as legend has it, he told Escoffier, "I am the Emperor of Germany, but you are the Emperor of Chefs." This was quoted frequently in the press, further establishing Escoffier's reputation as France's pre-eminent chef.[6]

Ritz gradually moved into retirement after opening The Ritz Hotel in 1906, leaving Escoffier as the figurehead of the Carlton until his own retirement in 1920. He continued to run the kitchens through World War I, in which his younger son was killed in active service.[4] Recalling these years, The Times said, "Colour meant so much to Escoffier, and a memory arises of a feast at the Carlton for which the table decorations were white and pink roses, with silvery leaves – the background for a dinner all white and pink, Borscht striking the deepest note,Filets de poulet à la Paprika coming next, and the Agneau de lait forming the high note."[7]

[edit]DeathEscoffier died on 12 February 1935, at the age of 88 in Monte Carlo, a few days after the death of his wife.

[edit]Publications

- Le Traité sur L'art de Travailler les Fleurs en Cire (Treatise on the Art of Working with Wax Flowers) (1886)

- Le Guide Culinaire (1903)

- Les Fleurs en Cire (new edition, 1910)

- Le Carnet d'Epicure (A Gourmet's Notebook) monthly magazine published from 1911 to 1914.

- Le Livre des Menus (Recipe Book) (1912)

- L'Aide-memoire Culinaire (1919)

- Le Riz (Rice) (1927)

- La Morue (Cod) (1929)

- Ma Cuisine (1934)

- 2000 French Recipes (1965, Translated to English by Marion Howells) ISBN 1-85051-694-4

- Memories of My Life (1996, from his own life souvenirs published by his grandson in 1985 and translated into English by L. Escoffier, his great granddaughter in-law), ISBN 0-471-28803-9

- Les Tresors Culinaires de la France (2002, collected by L. Escoffier from the original Carnet d'Epicure)

- ^ Claiborne, Craig & Franey, Pierre. Classic French Cooking

- ^ Gillespie, Cailein & Cousins, John A. European Gastronomy into the 21st Century, pp. 174-175 ISBN 0750652675

- ^ Brigid, Allen. "Ritz, César Jean (1850–1918)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edition, May 2006, accessed 18 September 2009

- ^ a b Ashburner, F."Escoffier, Georges Auguste (1846–1935)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, May 2006, accessed 17 September 2009

- ^ The Times, 13 February 1935, p. 14

- ^ James, Kenneth. Escoffier: The King of Chefs., 2006. ISBN: 1852855266

- ^ The Times, 16 February 1935, p. 17

- Chastonay, Adalbert. Cesar Ritz: Life and Work (1997) ISBN 3-907816-60-9.

- Escoffier, Georges-Auguste. Memories of My Life (1997) ISBN 0-442-02396-0.

- Shaw, Timothy. The World of Escoffier. (1994) ISBN 0-86565-956-7.